‘No politics in the classroom’ shouldn’t prevent teachers from stating their support for marginalized students.

Which of the following is too political to be displayed in a public school teacher’s classroom?

- We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.

- One nation, under God, with liberty and justice for all.

- O say does that star-spangled banner yet wave o’er the land of the free and the home of the brave?

- I have a dream that my four children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin, but by the content of their character.

- Black Lives Matter.

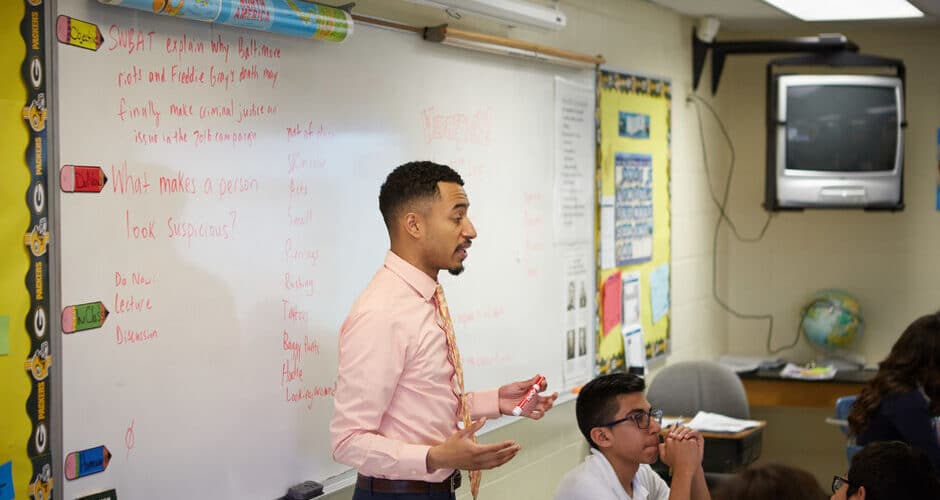

This question exemplifies the challenge of the surprisingly potent “no politics in the classroom” mindset that has led to pushback against educators’ efforts to make students feel welcome, protected, and embraced. Teachers are facing heat for displaying #BlackLivesMatter posters in their Bitmoji classrooms in Georgia and Texas, forcing us to consider a crucial question: How can “no politics in the classroom” work when education is inherently political?

To be clear, it makes sense that educators should not be communicating or vividly displaying outright support of political candidates in their classroom environments, because let’s be real: For every teacher who might wear a t-shirt supporting the same presidential candidate as I do, another teacher could be wearing the t-shirt of an opposing candidate whose policies I abhor.

However, most teachers in the hot seat for so-called “political speech” in the classroom are not getting in trouble for outright support of electoral candidates. Instead, the speech that causes outrage, censorship, and accusations of divisiveness tends to involve political beliefs: a teacher with a sign up that says, “No humans are illegal.” A teacher hanging a rainbow pride flag in support of LGBTQ+ rights. And a teacher wearing a #BlackLivesMatter t-shirt.

School systems concerned with preventing or addressing political speech have at least two challenging questions to consider: (1) what is “speech” in the context of a classroom teacher’s First Amendment rights and (2) what makes speech “political” enough to justify a disciplinary response?

>> This above is an excerpt from a piece that was written for Teach For America. To read the full article, go there now. <<

Leave a Reply